Washington’s Housing Attainability Crisis

Ramifications of the Underproduction of Housing Units, 1990s to 2020

Introduction

Policymakers, media correspondents, and a wide array of government rulemaking bodies have relied upon the Up for Growth’s study on underproduction

in Washington state for their estimate of the number of homes the state has failed to produce. Their estimate of 225,600 units underproduced is a great figure for referencing the scope of the problem.

However, the study only analyzed the imbalance between 2000 and 2015. BIAW sought to expand on this study to provide a more accurate estimate of the actual housing shortage in the state.

We will discuss our methodology, results, and any policy considerations that policymakers can utilize to combat the underproduction of housing units.

Methodology

BIAW utilized the same methodology that was employed by Up for Growth but applied the formula to the housing market from 1990 to 2020. The goal was to more accurately estimate the number of housing units the state has failed to produce in the last 30 years. We were then able to use the same forecasting model to then estimate how many housing units the state would be short if modifications to policy are not implemented.

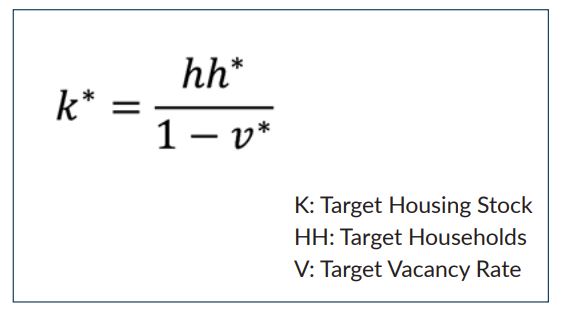

Key data points necessary for completing formulaic calculations include:

- Number of households

- Forecasted number of households

- Vacancy rate

- Target vacancy rate (for a balanced market, total housing units should sit at 13%, according to FreddieMac)

- Housing stock

- Target housing stock (relative to the number of households)

We then employed the following formula to replicate the study:

For background information regarding further calculations in relation to each variable, please refer to the “Sources” section and locate the “The Housing Supply Shortage: State of the States” publication. The results of our findings will be discussed in the following pages.

Results

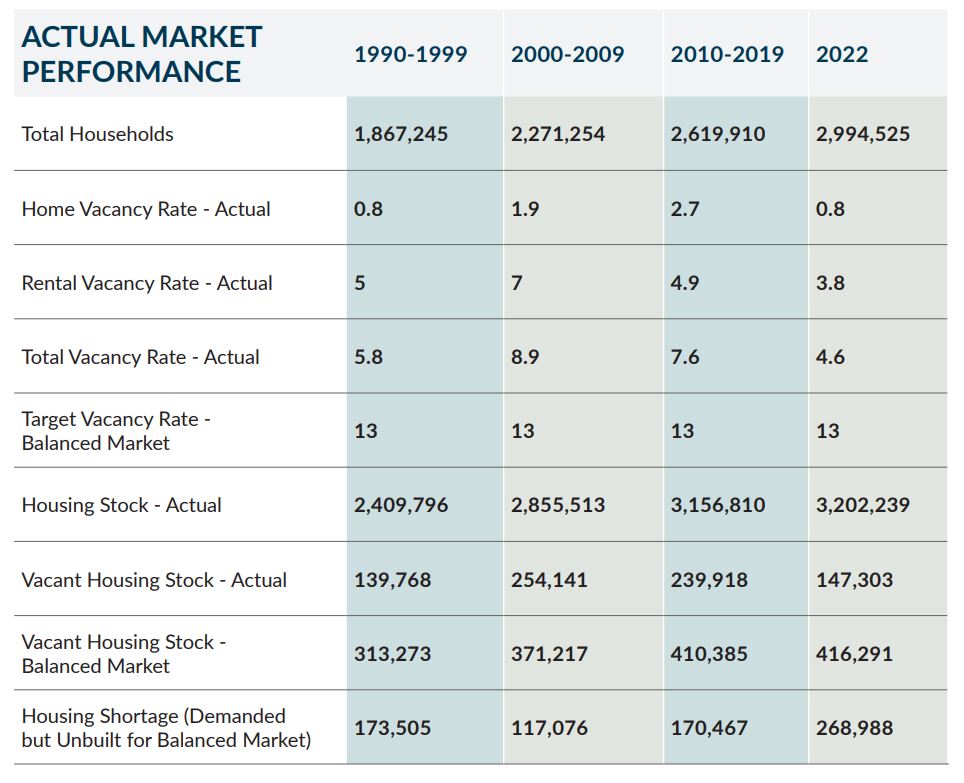

As of 2020, Washington has a shortage of 268,988 housing units. As we can see, that is a difference of 43,388 housing units not accounted for in the Up for Growth report. Since 2015, housing construction has increased but not at the level needed to meet demand.

The number of housing units constructed have not kept up with demand for housing units, as Washington’s population has exploded since the 1990s. In the last 30 years, the state has increased its population by 60%, yet housing units produced have only increased by 33%.

When we look at actual housing stock versus what is needed for a balanced market, we can see that no decade in the last 30 years has produced enough housing units to achieve a balanced market. In fact, the gap has continued to widen between actual vacant housing units and what’s needed for a balanced housing market.

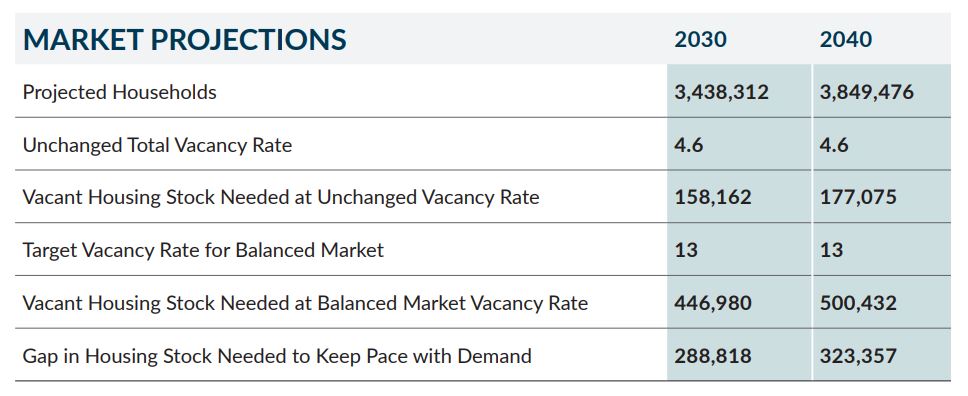

Our forecast for 2030 and 2040 illustrates the shortage of housing units the state will have if the current trajectory continues. In 2030, we can expect the shortage of housing units to increase to 288,818 and to 323,357 in 2040.

Some policymakers improperly attribute the number of building permits with actual housing construction. However, from 1990 and 2020, 1,277,499 permits were issued for housing construction. A factor that affects actual start and completion of permitted projects include:

Abandoned Projects

Construction is sometimes abandoned after permits are issued either before or after construction starts. Abandon rates fluctuate over time due to economic conditions such as the Great Recession time period of December 2007 – 2009.

Misclassification

Permitting agencies sometimes incorrectly classify permits as new residential construction when the permits are actually for smaller home improvement projects, non-residential structures, or mobile home authorization.

Design Changes

Builders can make design changes after the original issuance of permits. This typically occurs with apartment buildings where the number of housing units authorized by permits can fluctuate, resulting in more units constructed or less.

Change in Inventories Between Time Periods

The number of units that are authorized but not yet started affects the relationship between permits, starts, and the number of completed housing units. If construction is stalled for a significant period of time, a housing unit won’t hit the market until it’s deemed complete.

For single-family units, the U.S. Census Bureau has found common trends that affect the relationship between permits, starts, and completions. For example, single-family construction starts are typically 2.5% greater than permits issued, and completions are generally 3.5% less than starts in the same year.

Policy Considerations

When homes are in short supply, families pay more or are pushed out of the communities in which they grew up. Policymakers can utilize the following strategies to help spur more residential development in their communities:

Modernize outdated zoning regulations

Single-family homes are important but our state also desperately needs ‘missing middle’ types of housing to fit the diversity of households. Townhomes are a great option for many communities to increase density while simultaneously keeping community character. With millennials entering the prime homebuying age and the wave of baby boomers looking to downsize, these structures will help alleviate the massive shortage of homes we have for our citizens.

Reform project approval processes

Stakeholder and community engagement are important but this should be balanced with the need to build more housing units. Allowing citizen activists to stop housing projects on the basis of ‘Not in my Backyard’ arguments should be balanced with the community’s need to provide housing for all.

Accelerate the permit process

Planning departments should consider expediting new housing construction permits. Whether that is creating a separate permitting process for some housing types (like the ‘missing middle’ structures) or investing in automated software to reduce time spent passing papers between hands, any innovations that help streamline the process would help increase housing starts and completions.

Re-assess the effectiveness of impact fees

Reasonable impact fees are important to offset the cost of the infrastructure it takes to support more citizens. However, these fees can vary between jurisdictions and can impact the decision of a housing developer to build housing in jurisdictions with moderate to high impact fees. Impact fee deferrals or decreases in fees should be considered to increase housing construction.

Design standards and building codes

Design standards and building codes that go above and beyond protecting the health and safety of occupants should be scaled back until the housing supply imbalance is improved. Dictating the materials and appliances that must be used in the construction of housing only increases the cost paid by the developer and the end-buyer and works to price-out families from the right to shelter themselves.

Get hard on jobsite theft

Jobsite theft is a hidden cost of doing business for housing developers. However, every theft means replacement of tools, materials, and possible increases in insurance premiums for the contractor, which in turn adds cost to new housing units. Further, if a community is known for high rates of jobsite theft, developers won’t build there. Investing in policing activities that better protect residential project sites from theft will help the housing shortage.

There is no silver bullet to the housing shortage. However, if utilized, these strategies can help combat the massive shortage of homes available for Washingtonians.

Sources

- Khater, Sam, Kiefer, Len and Venkataramana Yanamandra. (2021). “Housing Supply: A Growing Deficit.” FreddieMac: Economic &

Housing Research. Retrieved from https://www.freddiemac.com/research/insight/20210507-housing-supply - Khater, Sam, Kiefer, Len and Venkataramana Yanamandra. (2020). “The Housing Supply Shortage: State of the States.”

FreddieMac: Economic & Housing Research. Retrieved from https://www.freddiemac.com/research/insight/20200227-thehousing-supply-shortage - Urban Institute. (n.d.). “Forecasting State and National Trends in Household Formation and Homeownership.” The Urban

Institute: Housing Finance Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/housing-finance-policy-center/projects/forecasting-state-and-national-trends-household-formation-and-homeownership/washington - U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). “Building Permits Survey – Permits for Washington State, 1990-2020.” [Data Set]. Retrieved from

https://www.census.gov/construction/bps/data_visualizations/ - U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). “Housing Vacancies and Homeownership.” CPS/HVS. [Data Set]. Retrieved from https://www.census.

gov/housing/hvs/data/histtabs.html - U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.) “Data Relationships between Permits, Starts, and Completions.” New Residential Construction.

Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/construction/nrc/nrcdatarelationships.html - U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). “Resident Population in Washington.” FRED Economic Data, St. Louis FED. [Data Set]. Retrieved from

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WAPOP